Digitizing Salem Village

A Conversation with Benjamin Ray

Originally printed in the September/October 2000 issue of

Humanities: The Magazine of the National Endowment for the Humanities

When NEH Chairman William R. Ferris talked recently with Benjamin Ray, professor of religious studies at the University of Virginia, the conversation turned to technological advances in teaching and Ray's work on the Salem Witchcraft Project. Ray's books include African Religions (1976) and Myth, Ritual, and Kingship in Buganda (1991). He is the Daniels Family Distinguished Teaching Professor of Arts and Sciences.

Ferris:I understand that you had ancestors in Salem Village and that they were involved in the witch trials. What was your family connection and did it inspire you to study these trials?Ray:It was just a few years ago that I actually paid any attention to that family connection. I'm an Africanist and work generally on a different continent, so it wasn't something I was looking into either in a scholarly way or as family history until I went to pick up my daughter from college in Boston. My wife and I decided we would make a side trip to Danvers, which is the old Salem Village, and look up where my ancestors lived. I found some still-standing houses, which was amazing. One is a seventeenth-century house. I thought, "My goodness, there are actual buildings standing there that my ancestors lived in." So I began to look at the published documents a little bit more. There is an index and you can look up everyone's name, or almost everyone's name.Ferris:

I noted that my family's names were always listed mainly as defenders, which is something I hadn't heard about. You hear about accusers and the accused and the ministers and judges, but there were a number of villagers who were trying to save those who were accused by signing petitions, testimonials, on their behalf. Unfortunately, that had absolutely no effect, and some risk for the people doing it.That is amazing. You have obviously done a lot of detective work for the Salem project. What have you found?Ray:I'm working with a colleague. My job is the more technological side, giving access to this material. Bernie Rosenthal, who is in the English Department at SUNY-Binghamton, is the editor-in-chief of a new transcription of the court documents. There are about 850 court documents. The Puritans documented everything they did, both good and bad. This really tells the story of the people. You hear the voices of the accusers and the voices of the accused, the judges, the ministers, even occasionally some of the attendants. The most valuable kind of document is, in fact, not the arrest warrants and the depositions so much as the actual courtroom interaction where you hear those confrontations.

As I was looking in the archives in Boston, particularly at the Boston Public Library, I ran across some of these transcripts, which apparently had been overlooked by earlier scholars and transcribers. Just encountering those and transcribing them for the first time was pretty exciting. I think every historian is eager to find something new in a territory that has already been well worked over.

"You hear the voices of the accusers and the voices of the accused, the judges, the ministers, even occasionally some of the attendants."

Ferris:By putting the Salem Village court documents online, you are making them accessible to people all over the world. Who is using your site?Ray:Looking at the web statistics at the moment, it is educational institutions and individual members of the general public. It is about half educational and half the general public that has an interest and is looking for resource material.Ferris:What makes a web archive useful for students?Ray:We have a few search mechanisms. For example, a previous transcription of the court documents has been available since 1977, and although they're flawed and based on work during the WPA period of the Great Depression, they are nevertheless pretty good, and we have those online. For example, if you type in the word "witch," you will get every occurrence in what are approximately three volumes of documents. And for the first time, a high school student can write a paper on the subject of the concept of the witch in the trials, or the concept of the devil, or the concept of evil as it was used by judges and accusers and the accused. You can get a good handle on this conceptual terrain and what was going on that was so inflammatory at that time.

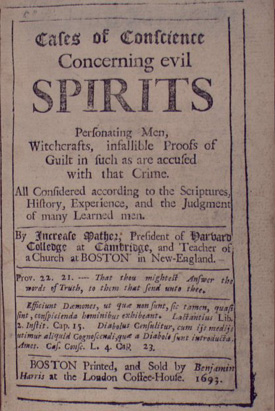

Title Page of Increase Mather's Cases of Conscience Concerning Evil Spirits..., 1693

Reproduced with permission, University of Virginia Special Collections Department

Ferris:How has the Internet changed your work as a historian?Ray:There are several things going on. We are using the Internet to provide access to materials that have been difficult for our students, let alone the general public, to work with. A colleague of mine in the history department has taught a course on the Salem witch trials only once in the twenty years that he has been here, even though he is a Puritan historian, because you can't really get these primary sources into the students' hands for them to get excited about unless you have every student owning three volumes of court documents, which are in fact out of print. So it has been difficult to teach this subject except by secondary sources. What's exciting for historians is to put primary source materials in the hands of the students so they can participate in the kind of scholarship that scholars do. You can then teach the craft of scholarship, whether it is history or any other subject.Ferris:One benefit of the Internet is that you can combine text and images in new ways. How do the interactive maps on your website help understand who is being accused and who is doing the accusing?Ray:

"The Trial of George Jacobs, August 5, 1692." By T. H. Matteson, 1855. Oil painting.

© Peabody and Essex Museum, and used here with permission.That is another exciting feature -- the ability to put text and graphic images together. Sometimes those images are contemporary with the text and other times they are decades or a century or two later. That is one of the goals of the NEH-funded project: to create a history of the images so you can understand how in different periods the images themselves are functioning as interpretations.Ferris:

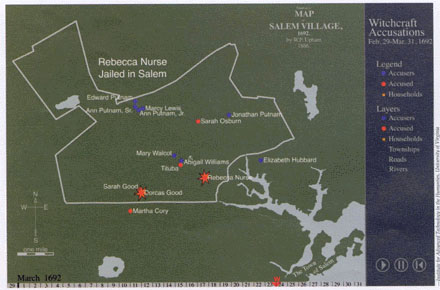

What we have done, too, is provide maps to help give a graphic representation of historical context. It is hard to envision what a village is like on the ground, where people are living. If you click on households on the map you'll see all the households spring into view. It shows a rather large population of about five hundred people living in the households.I see that, too.Ray:If you want to know something about the accused slave who is named Tituba -- the red dot on the "Salem Village" map -- she was one of the first accused, and you click on the red dot, the screen opens up with a list of the members of the household and the biography and some documents and images.Ferris:

An interactive map from the website displays bursting stars for individuals on the day they were accused. Clicking on the dots links browsers to biographical pages.

Reproduced with permission, University of Virginia's Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities

The Reverend Parris is the minister of the village meetinghouse. And it shows several accusers in that family, as a matter of fact. Elizabeth Parris, with her birthday there, you see she's only ten years old. And then her cousin -- and we will have genealogies attached to this -- is Abigail Williams. She is the niece of Samuel Parris and the cousin of Elizabeth. She is an accuser, too.

This is the kind of thing I like. You go to images and click and go to the illustration of Tituba's encounter with the famous Puritan clergyman Cotton Mather. So here you have the fair-skinned, fair-haired young Cotton Mather encountering this image of an elderly Native American woman with her basket full of herbs, scowling and looking very mean. If you go to Tituba in image number two, you see something quite different. This is a 1997 image from a juvenile book. Tituba is no longer an elderly Native American. She is a young African American, with the girls fascinated with her divination, which uses an egg white in a glass.

These images through time relate to both oral tradition and actual text traditions. We can link texts with these and the surrounding context of how the American imagination has dealt with the episode across time, including racial, ethnic, and gender perceptions.There were all sorts of explanations for what happened in Salem. Some said that independent women who lived alone, like widows and midwives, were accused of witchcraft because their neighbors coveted their property. What do you think caused the whole incident?Ray:We will always be attracted to the theory that weights the cause in one direction. It is like the McCarthy trials, which Arthur Miller wrote the play The Crucible to reflect upon. There is a nexus of factors that allowed this to happen. You have neighbors with grudges. You have ministers who were eager to seek a revival of faith and religious authority. You have judges, particularly the chief justice, who had a political interest -- he had his eyes on the governorship. You have petty disputes among families living in the villages. You have a new charter for the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and a little uncertainty about how to proceed. A lot of features together make what is absolutely a unique event.Ferris:

This number of accusations never occurred before; the situation became out of control. It ran all up and down the social ladder, which was unusual. Why such a broad range and such a broad scope?

It wasn't just the village. Twenty-seven people in Salem Village were accused. In the village of Andover, there were forty-seven. In the town of Salem, there were seven. Up as far as Wells, Maine, and down to Boston, more than 150 people were accused. So you have a large area of Massachusetts Bay that is involved, too, making any one explanation a little too simplistic for a complex phenomenon.Your website builds on research that was done in the late thirties and funded by the WPA. How did the WPA project come about?Ray:I'm not sure how that came about. It was funded by the WPA program, but it was a clerk of courts in Essex County that oversaw the actual transcription and the collection together of the documents so they could be transcribed, a wonderful recovery because some of these documents, the originals, have now been lost since that 1938 transcription. They existed in typescript, and in 1977 they were put out in published form. That created a watershed of scholarship.Ferris:

The web presentation will extend the possibility of more scholarship, perhaps more fine-grained, through the search engines and through the placing of texts, images, demographic, and genealogical data together on this site. We will put in those firsthand eyewitness accounts. There also were six books published, and we are putting those online in original page images -- there were sometimes only three or four copies -- and digital texts that can be searched.How does your project add to the WPA transcriptions?Ray:In almost any of the transcriptions you look at, there are a few mistakes, many of them minor. But as the editors begin working on it, they have found some major whole lines and sentences left out, and wrong dates, which change the meaning of the document. We will be putting on updates over a period of two or three years as the international team of editors works on the new transcriptions, and we are putting up many facsimiles, scanned, of the originals so that a viewer can look at the original document and see some of the issues involved as the editors work on them.Ferris:When you do a search on the Internet for words like witch and Salem, you get a list of sites dealing with everything from pagan religions to Sabrina, Teen Witch. How does your site debunk or correct this mass of information?Ray:That was one of the motivations. Initially, I wanted to provide resource material for teaching a seminar for religious studies majors. As I made a check on the web, I discovered there is everything under the sun out there, and very little is reliable. This gives depth historically.Ferris:

That is what the University of Virginia Electronic Text Center is dedicated to, putting texts online and maintaining them. This archival site won't go away.That's wonderful.Ray:It will be maintained for scholars in perpetuity. That is just part of the new direction of digital libraries, digital research.Ferris:Tituba, the first person accused of witchcraft in Salem, was a slave from Barbados. She confessed that she was a witch, and several books telling her story have come out recently. Is it true that Tituba was a Native American and not born in Barbados?Ray:There is not a whole lot of evidence to help us. She is said to have come from Barbados with the Reverend Samuel Parris, who was the owner of a sugar plantation, which failed, and he sold it. It is said that the two slaves he brought with him, Tituba and her husband John, were from Barbados, but they were always referred to in the court documents as Indians. Consistently, there are numerous documents specifying her name and following it with the word "Indian." The Puritans differentiated between African Americans, and they were slaves, and those that they called Indian, who I assume meant Native American. But a little bit beyond that, you can't go. They never called her black and never called her African, which is the term they use for several of the slaves who appear in the witchcraft documents.Ferris:

One of the issues, on the other hand, is simple to resolve: What kind of witchcraft did she know about, or what kind of divination was she teaching, if she taught the girls in the Parris household? Was she teaching something that we can now identify as, say, culturally African or Caribbean? The answer to that is quite simple: No. If she were involved at all in teaching the method of divination, what she was teaching was European, the egg white in the glass of water. As the egg white sinks into the water and swirls around and you look in the glass, it's kind of like a moving Rorschach, and that is a European technique. Riding on a pole in the air, which she confesses to, is also a European idea. And seeing witches in the woods in some kind of ritual context is also a European idea. So all of the documents give us information about her, and what she was doing and her knowledge of anything related to witchcraft or divination indicates it was European and not West African. As an Africanist, that's pretty clear to me.How much did race and class have to do with who was accused of witchcraft?Ray:Not much. Apart from Tituba and two or three others -- Mary Black -- there weren't too many slaves mentioned in the documents, and very few of them were accused. The accusations generally fall along lines of previous social conflict between families who are in either positions of power and are contesting each other or are contesting property, as you mentioned, or they're contesting relationships they have in the church or other relationships.Ferris:

Rebecca Nurse before the magistrate, illustrated by F. A. Carter and appearing in John R. Musick's The Witch of Salem or Credulity Run Mad.

Going up the social ladder, you have another group of people accused: Those are people who are beginning to object to the trials, even the governor's wife. John Alden, son of two rather famous figures, Priscilla and John Alden, becomes caught up in the accusations because he's an Indian fighter. The rumors are that he also had Indian women and some sort of relationship with them; those rumors get translated into accusations. So it spreads around the whole social ranking system pretty quickly.What was the common definition of witchcraft in the seventeenth century?Ray:That's easy: a covenant with the devil. It was the mirror image of the covenant the Puritan was to make with God. Becoming a member of the Church was something you did as an adult. You signed a book of membership after being examined by your minister in the presence of the congregation and by affirming your kind of experiential, spiritual encounters with God, with Christian teachings in your life.

The reverse was true, then, with the devil, throughout the documents. The devil would present a book, and you were to sign it. This was an act of not just religious aversion, but since it was a theocracy, a political aversion, so it was an act of betrayal. For that, if you were guilty, you were beyond the pale. The condemned witches were not buried in cemeteries. They were outcast. They were executed outside the town, beyond the borders of the community, because they were agents of a subversive force.

"Even in the prelude to Salem, some girls in Boston were going through physical gyrations and verbal abuse, and accusing people."

Ferris:In Europe, between the fourteenth and eighteenth centuries, more than one hundred thousand people were accused of witchcraft and many were put to death. How does the Salem witch-hunt compare with witch-hunts in Europe?Ray:I wish I was more of a European historian.Ferris:

In New England, the accusations were very local, only two or three people, and the judges and the clergy were most concerned to control the accusations and to dampen down this avenue of social redress. Even in the prelude to Salem, some girls in Boston were going through physical gyrations and verbal abuse, and accusing people, and Cotton Mather was most concerned that they did not begin to attract others to make similar accusations. There was a general attitude of damping down accusations when they occurred and not acting on them so that it would inflame others.

In Europe, you have larger numbers accused, and it is much more tied up with state and church-political institutions -- until Salem. In Salem, there were more accused than ever had been in the history of New England, and even more executed. That is what has attracted scholars, what happened in Salem. The accusations started at the end of February 1692, and before they were stopped in November, there were about 150 people in the jails.Arthur Miller created a vivid image of seventeenth-century Salem in his play The Crucible. The witch-hunt is now an icon in the public imagination. Will your website disillusion people only acquainted with Arthur Miller's version of the story?Ray:There is a website that I've come across that is pretty good at dealing with the differences between his play and historical events in Salem. His play is very effective, obviously, and he has taken literary license with history, which I think is fine to make a unified, effective dramatic piece.Ferris:

I think what you get in the documents is as riveting as in Miller's play when you read the voices of the accusers and the accused. They claim their innocence in a dramatic form and assert themselves almost against both church and state. They are thinking: Before God I am innocent, and something has gone off the rails here. The church and the state are going in the wrong direction.

The dramatic voice of those courtroom scenes comes through as strongly as in the documents as in Miller's slightly adapted version. In Salem today re-enactors perform segments of the court trials, lifted right from the actual words of the documents.The Salem witch trials have fascinated Americans for centuries, and there is a wealth of literature inspired by the historic events. Why do you think this period of history inspired such an outpouring of creative work?Ray:It is hard to reconcile -- our view of America as a land of freedom to which people came who were fleeing persecution and to discover that, at least in Massachusetts Bay, those very people set up a system which could eventually become a system of persecution of the kind they fled. It stands as an aberration of what we think of as our founding principles. And it is a gripping story of heroic victims -- mainly women -- and vengeful persecutors, both male and female, young and old.Ferris:

I never knew of the interest in Arthur Miller's play, to the Salem events, until I happened to talk with friends who live in Europe, where the play is regularly performed and resonates there, too, in a way that relates to their experience in the former Soviet Republic, for example, in Latvia.How would you say that the witch-hunt is still relevant for us today, four hundred years later?Ray:It is not that history repeats itself exactly, but you see a microcosm of a moment of crisis in which people are making decisions as to where they're going to stand in this vital moment. That is very instructive for any time.

"This technology is not a way of necessarily teaching more with less, as some might fear in other schools, but teaching better, and exciting your faculty about the possibilities."

Ferris:Absolutely. I can't tell you how exciting it is to see what you and your colleague, Ed Ayers, are doing with the mixing of technology and scholarship in such creative new ways. I wonder if you could reflect on that. There are not many places like Charlottesville and the University of Virginia that have that nexus of different worlds converging and creating what we might think of as a new breed of scholarship.Ray:Somebody said that there is "something in the water in Charlottesville," where we've taken technology and tried to use its tools to extend and to enliven the educational mission. I think it has to do with the commitment at various levels of the university from the top down, the president's office, from alumni donors who are excited, from institutions. IBM started contributing, and Xerox Foundation did. They were looking for institutions who might be interested in technology. A member of the engineering school said to IBM, "Why don't you put some technological machinery in the humanities area? Let's see what will happen when you do that." Ed Ayers saw the potential and his example then led others to take a look. We have developed programs for the classroom, a teaching and technology initiative. We have developed programs for faculty research projects at the Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities, which is supporting the Salem project. It has caught on through a few good examples and wonderful institutional support. This technology is not a way of necessarily teaching more with less, as some might fear in other schools, but teaching better and exciting your faculty about the possibilities. That is why it has caught on, I think. It has excited us about teaching and research. Ed and the rest of us are as excited about how we can apply it to our classrooms and our students as we are in advancing purely scholarly goals for the community of scholars. Our work is aimed both at research as well as application in the teaching mission.Ferris:It is really a thrill to see it.Ray:Next spring we will involve students in helping us think up the interface, that is, think up interesting and attractive ways that will turn students loose. We are creating a database that will enable them to query the database and ask questions and get tables and answers in response. We are quite excited. When you put in genealogy and demographics and social ranking together with text documents and images and search engines, we don't know what we will come up with.Ferris:It will be very interesting. I want to congratulate you on the wonderful new frontiers you are opening up for all of us.Ray:Well, thank you a lot for the interview. I appreciate it.

Sidebar:

The Many Manifestations of Tituba

A scene from the play Giles Corey of Salem Farms by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Illustration by J. W. Ehninger.

Illustration by Robert Gantt Steele in Priscilla Foster: Story of a Salem Girl, by Dorothy and Thomas Hoobler.

In Tituba's Encounter with Cotton Mather in the woods of Salem, by J. W. Ehninger, Tituba is depicted as an elderly American Indian woman. In the children's book illustration by Robert Gantt Steele, she is a young, energetic African American girl. In Maryse Conde's I, Tituba, Black Witch of Salem, excerpted below and translated with NEH support by Richard Philcox, she is portrayed as an African American woman. Tituba's actual ethnic origins remain a mystery to this day.Then Goodwife Parris told me what was going on in the village. "I can only compare it to a sickness that first of all is thought to be benign because it affects the lesser parts of the body . . ." Lesser parts? It's true that I was only a black slave. It's true Sarah Good was a beggar. So great was her poverty that she had to abstain from coming to the meeting house for want of clothes. It's true that Sarah Osborne had a bad reputation because the Irish immigrant she had hired to help her on the farm quickly advanced from the widow's barn to her bed. But even so, it was shocking to hear us coldly described as "lesser parts."